Yesterday I visited the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. It is the home of the famous U.S. Space Camp and, at the nearby Redstone Arsenal, NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. Since space flight is predicated on rocketry, Marshall is arguably the birthplace of the American space program. At Huntsville America took the shameful remnants of Hitler’s missile program and transformed them into an ideal of peaceful, civilian-controlled scientific achievement, culminating in the landing of men on the moon. The centerpiece of NASA’s effort, and indeed the showpiece of the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, is the Saturn V rocket.

To a certain kind of person, one like me, standing under this massive machine, the most powerful vehicle ever built, fills the heart with pride. Every patriotic American should be proud of what this country achieved, ostensibly to beat the Russians, but truly to advance science and answer the fundamental questions men have posed since our ancestors first looked up at that bright light in the night sky.

Since the Saturn V is a superlative machine, let’s say the superlative machine, I cannot help, at this point, offering some data to back up that claim. The Saturn V, fully assembled with the Apollo capsule in place, stood 363 feet high. Loaded and fully fueled the Saturn V weighed 6,500,000 pounds (3,250 tons). For reference this is the weight of about 7 Boeing 747s. The fully loaded weight of the Saturn V represented a great deal of fuel. After liftoff the five powerful F1 rockets burned for 2 minutes and 41 seconds, each generating 1,500,000 pounds of thrust. In that time those engines consumed 4,700,000 pounds of fuel (Kerosene and liquid oxygen). In terms of energy released as a function of time, this makes the Saturn V a bit like a scarcely controlled bomb. In 161 seconds the Saturn V burned 82% of an Olympic swimming pool of fuel.

So that is pretty big and pretty powerful and pretty god-damned amazing and yet …

Apparently, according to the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, the most powerful machine ever built is an inadequate showpiece to hold the attention of entertainment-starved Americans and get them to part with $27 in the museum gift shop for a flashing Chinese-made keychain with Katelyn, or Caitlin, or Katylynne printed on it. To buttress the Saturn V and the Jupiter C and the Mercury-Redstone and the full-size mock up of the Space Shuttle and, get this, an actual, no-kidding rock from the frigging moon they needed something “flashy.” So, right in the middle of this monument to American can-do technological know-how we have – a carnival ride. No, here are two carnival rides. No, wait, three. Here my internal curmudgeon shows his wrinkled face. Since cell phone addled kids can’t be expected to focus on something as humdrum as a 363 foot tall rocket there is a ride called the “G-force” or something suitably “spacey.” The G-force, pretending to be an “astronaut-training device,” is nothing more than the ride we used to puke all over at Adventureland called the “Silly Silo.” Next to it is a “temporarily out of service” launch simulator named the “Space Shot” which is no more than the kid’s “bouncy ride” from the Mall of America.

And I suppose the amusement park philosophy at the U.S. Rocket center is actually market driven; gotta pack in the paying customers. But why must everything in this country, including a museum dedicated to our space program have to turn a profit? I soon saw why. As I was standing in the main hall taking in a captured German V2 rocket, a disgusted father and his tween son hove into view from the IMAX theater (another concession to entertainment culture.) The father, about my age, tried to engage his son in the wonder of the Saturn V. The son continued to groan and send text messages on his phone. A bit later I saw the father literally throw up his hands and say, loudly, “So this is how today’s gonna go, I guess! You are going to refuse to be impressed by anything?”

I am not, at all, prone to picking on the Millennial generation. My children’s cohort, the ones I have known, are intelligent and savvy, and hard-working. They are achieving some amazing things against the strong headwinds of a tough job market, low pay, and crippling college costs. They face challenges that my generation and my parents generation never faced and indeed “laid on them.” What is sad, to me, is that we have failed to inspire these kids with the science and technology that set our hearts afire. More on that later.

Unlike the tween boy I found much to be impressed by at the U.S. Rocket Center. Exhibits in the main hall included the Saturn V, the aforementioned moon rock picked up by Astronaut Alan Bean, an actual piece of Skylab the size of a Mini Cooper which survived its plunge to Earth when it crashed into Australia in 1979. There were models of the U.S.’s past and (hopefully) future rockets, “extra” F1 rocket engines, and a full scale mock-up of the lunar rover demonstrating the manner in which the little space car could be folded into a box about half its size. In the corner stood an actual Apollo spacesuit. It looked just like my grade school friend had described the one he owned and “forgot” (so many times) to bring to school to show us. All of these wowed me. I found myself lapsing into vivid daydreams starring me, lying in that implausibly small capsule atop that pillar of explosives and being catapulted into orbit, watching the wide green horizon of Earth resolve itself before my eyes into a curved blue billiard ball framed by blackness.

I have, several times in my life experienced what Edgar Allan Poe called “The Imp of the Perverse,” a powerful, nay overwhelming, urge to do a dangerous, forbidden, and completely uncharacteristic thing. My imp presents himself mostly at moments of awe or grandeur, or at times when circumstances call for decorum. I felt his presence when I stood on the observation deck of the Empire State Building and heard his whispered voice describing to me the perfect swan dive one might execute for the crowds below. My imp gnawed at me yesterday as I stared at the moon rock, urging me, prodding me, tempting me to lift up the glass enclosure and pick up this otherworldly relic. I had to walk away eventually, out of fear.

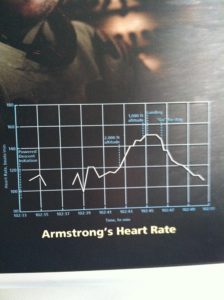

Nearby was a fascinating exhibit which showed Neil Armstrong’s heart rate during his manual landing of the Apollo 11 lunar module. Even Armstrong, whom I always found to be disappointingly boring in interviews, could not hide the pressure and excitement of the mind-blowing activity in which he was engaged.

Outside the rocket center’s main exhibit hall are some other pretty amazing pieces of American-made technology, now left to moulder. The A12, an early model of the SR-71 sits, apparently rusting if such a thing is possible, in front of the gift shop. This is an aircraft capable of traveling from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C. in 64 minutes. Today it was going the opposite of fast. It needed a thorough cleaning to remove the pine pollen and a coat of paint.

Behind the visitor center and flanked by the carnival rides were rockets representing the critical baby steps it takes to get to the moon. There was the Mercury-Redstone rocket, America’s desperate attempt to catch-up to the Russians and put a man “up there.” The Redstone part was simply an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) with the warhead replaced by a capsule the size of a pup tent. When ready for launch it resembled nothing so much as a high powered rifle cartridge with Alan Shepherd the little lead projectile on the end. The courage it must have taken to climb into that claustrophobic bullet and be launched into space makes Schwarzenegger look like Shaggy from Scooby-Doo. Why can’t we sell this story to kids? Why do we need gimmicks and rides to hook kids on science? We have actual heroes and actual amazing machines to inspire the next generation. The other rockets, like the A12 are fading in the hot Alabama sun. Their chalky paint looks like my old ’87 Mercury Sable. Even the signs and placards meant to explain these wonders to the center’s visitors are faded and warped and unreadable. In the meantime the Space Camp kids, whose parents are paying thousands of dollars to send them here, are treated to the Silly Silo and a foil package of Astronaut Ice Cream. We should do better.

We are so cheap in this country now and have lost our collective swagger to the point that we have to pay the Russians to send our astronauts to the International Space Station. What we can do, apparently, is make movies. Finally, overwhelmed by the heat, I retreated into the visitor center again to take in the IMAX movie. This movie had the highest ratio of flag-waving pride to things to be proud of I’ve seen since the last time I was in Texas (sorry Texas, that was a cheap shot). It crowed about our past glories, Mercury, Gemini, Apollo. But then it lapsed into cheap sci-fi, commercialism, and wishful thinking. Part of the film was little more than an unpaid advertisement for Spacex (Elan Musk’s commercial rocket launch company) and it’s competitors. A breathless narrator explained how these highly-subsidized private companies would be doing the basic “Earth orbit” stuff in future so NASA could focus on dreamy stuff like a trip to Mars in the next 30-100 years.

I’m sorry guys. That model does not inspire one kid to study Physics. It is not a vision we can all take ownership of and be proud of like Apollo was. And don’t fool yourself; unless the American public is inspired and unless they feel real pride and ownership in our space program none of this stuff is going to happen. If kids can’t go down to Cape Canaveral and feel the vibration in their chest as a Space Shuttle roars off the launchpad with a big American flag painted on the side, there will be no money for space flight and there will accrue none of the tangible and intangible benefits of space flight we got from Apollo.

When I walked out of the U.S. Rocket Center with a strange combination of inspiration and disappointment I waited near the curb for my hotel van. To my right, near the entrance, was a specially marked parking spot blocked for use, so the sign said, of the U.S. Rocket Center Director. Parked in the spot was a shiny new Tesla sport’s car, manufactured by Elon Musk’s other flagship company. I do not imply here a quid pro quo. I will allow you to draw your own conclusion. It is possible that the Director, obviously a space enthusiast, is simply a fan of Musk and his technologies (I am, too). All I am saying is that if the U.S. Space Camp is in the business of promoting private space initiatives while NASA dreams unfunded dreams we have lost our way.

Not everything we do as a nation requires a profit motive. Some things should be done because they are intrinsically worth doing. They are worth doing because they inspire us, lift us up, give us a nobility of purpose. Doing these things together as a nation, instead of as companies watching the bottom line, bestows that nobility on all of us, rich and poor. When Armstrong made that step onto the powdery surface of the moon every American’s heart rate rose with his because we were all there with him.

by: Dustin Joy