In my last travel related post I told you of my experience at the U.S. Rocket center in Huntsville, Alabama and of my infatuation with the Saturn V, the most powerful transportation machine ever built and certainly one of the fastest. Today I found myself, unexpectedly, spending the greater part of a day in downtown Syracuse, New York where I became, if not infatuated with, at least deeply fascinated by another museum dedicated to a much slower mode of transport.

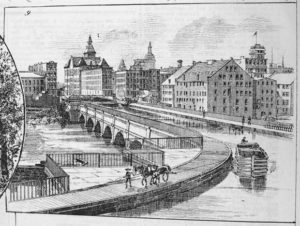

After an amazing lunch at the Creole Soul Cafe (who knew Syracuse, NY would have absolutely amazing cajun food?) I walked up to the Erie Canal Museum which lies on the aptly named Erie Boulevard. It turns out that the boulevard, now blacktop instead of water, was the route the famous canal took through Syracuse. The museum is part of the original Weighlock building where passing canalboats were, quite literally, weighed to assess their toll for canal passage.

Looking at a Saturn V rocket and the Apollo program in it’s entirety one can scarcely believe that this little ditch was its equivalent, perhaps it’s superior, in 1820. Considering the resources and technology of a still young nation this project was audacious. In fact, when asked to help with the financing of it Thomas Jefferson, no slouch in the visionary department, wouldn’t touch it with a ten-foot pole. “…little short of madness,” he is said to have commented.

It fell, instead to the Governor of New York, Dewitt Clinton, a bunch of progressive legislators, and some even more visionary but less celebrated thinkers and engineers to bring this crazy idea to life. And, like the Little Red Hen, when the wheat grew, was, harvested, ground into flour, and baked into a nice warm loaf, New York ate that loaf and became, well, New York.

Many big cities grow organically from a wide spot in a river. Clinton’s audacity was to build the river. Cities like Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Albany, and, to a greater extent the Big Apple, grew from these seeds.

If going to the moon seems like one giant leap (to quote Neil Armstrong) the building of the Erie canal, in it’s day, was no less improbable. To understand the difficulty it is useful to assess the terrain of upstate New York.

Starting in Albany the canal follows the course of the Mohawk River west. This makes a lot of sense. The more your route can follow existing rivers the less you have to dig. Also, to New York’s great good fortune, the Mohawk possesses a unique characteristic unknown to other eastern rivers. It flows east into the Hudson, but it rises west of the Appalachian mountains. It’s valley transects the one insurmountable obstacle which stymied so many dreamers intent on building a water route to the Ohio or the Great Lakes.

Minimizing the digging is not the only consideration for a canal, though. The Mohawk route made sense from a hydrological point of view, also. A canal is not a static system. Moving water is what makes the locks work and allows boats to change elevation. That means that water must be added to the system continuously from the highest elevations. Having rivers nearby makes that possible. Only sea level canals like the Suez are not subject to this requirement.

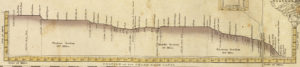

The Erie Canal route across upstate New York is emphatically not a sea level affair. Even with the advantage of the Mohawk, the elevation changes from Albany to Buffalo were daunting. The net rise from tide level on the Hudson at Albany to Lake Erie at Buffalo is about 600 feet. That’s just a little less than the height of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis. The best locks that could be constructed in 1825 would raise a boat about 12 feet. That would require about fifty locks, a big job. However, kind of like your Grandpa’s old story about walking to school “uphill both ways” the Erie canal route doesn’t just slope from one side of the state to the other. From Albany it goes up to about 420’ at Rome, then back down to about 380’ near Montezuma, then back up again at the Niagara River to 565’. In between it crosses rivers, creeks, valleys, and hills. The original “Clinton’s Folly” had 83 locks, each hand dug, lined with clay and stone, and fitted with heavy gates and valve systems. This was not child’s play.

Not a sea-level affair. A contemporary profile view of the Erie Canal route. Click on image for enlargement.

Looking at the map of the canal and upstate New York one is struck immediately by a question. You slap your head and think, “these people couldn’t have been that stupid.” The question is; Why build a canal across 363 miles of forests and swamps when you could, near Oneida Lake, cut a few miles up to Lake Ontario, ship your goods on this vast natural waterway to Niagara Falls, and build a short canal to bypass the falls? It is a good question, but there was, indeed, a method to the madness.

Firstly, canal boats are a great deal different from the sailing vessels required to navigate big open bodies of water like Lake Ontario. They are long and shallow draft to fit their highways of water. They are not designed to take big waves or make top speed under sail. So it would have been necessary to swap one for the other at Lake Ontario, again at Niagara Falls, and again to proceed on Lake Erie. If these dreamers had wanted to load and unload cargo three or four times they would have just kept transporting goods the way they had for years; overland in horse drawn wagons. Secondly, building a canal around the Niagara Falls, while doable (Canada did it in the mid-1800’s near Welland), was not an easy task. There is a reason Niagara Falls is such a famous attraction. It’s a damn 167 foot tall waterfall.

The truth is this though; It was mostly politics. In those days Canada was not the benign little puffball that we know today. Canada, or as they were in actuality then, England, was a very real existential threat to the new nation. We had just fought two wars against them and a multitude of skirmishes. It is easy to forget now, but was undoubtedly vivid in the American imagination then, that only three years prior to the commencement of canal construction, a British force had occupied Washington, D.C. and set fire to the White House and the U.S. Capitol. Only in September 1813 had the U.S. won undisputed control of Lake Erie during the famous Battle of Lake Erie which we all remember, if we remember it at all, from Oliver Hazard Perry’s cable to Washington after the victory, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.” The U.S. never did achieve decisive control of Lake Ontario.

To make a long story short we didn’t trust them, we didn’t like them, and we certainly didn’t want them to get the benefit and control of trade in the western Great Lakes. The New Yorkers spent extra time, extra money, and probably extra human lives to keep their new canal just out of reach of those dastardly Canadians. Thanks to their sacrifice we are not obliged to eat poutine three times a day.

Seriously though, building the Erie Canal was a matter of blood, sweat, toil, and tears. The claims of 1000 men dying of swamp fever (probably malaria) during the excavation through Montezuma Marsh in 1819 are probably exaggerated. Still, it is quite likely that many hundreds of men were crushed, drowned, lacerated, blown up with gunpowder, and killed by epidemics.

Consider, if you will, the difficulty of removing a single tree stump. Even today, with chain saws and tractors, and grinding equipment it is difficult, at best, to remove the stump of a large tree to below grade level. If you are digging a canal, grade level is not good enough. You must remove the entire stump including the tap roots. For a tree of considerable size, like the American Chestnuts comprising the primeval forest of upstate New York, these roots can go 20’ deep.

The engineers who met these challenges were clever men. The way they solved the tree stump problem tells you all you need to know about their resourcefulness. Below is a picture of their stump puller. It’s elegant use of simple mechanics and leverage is an inspiration.

The catalog of challenges faced by the Scots Irish immigrants who dug the canal, the German Stonemasons who built the locks, and the engineers who mapped out the route, were astounding. In building locks, bridges, aqueducts, and machines to do so, these men advanced science and technology in their age no less than did the NASA scientists who built the Saturn V.

Some of their achievements are truly astounding. There is, of course, the 363 mile long canal 40’ wide and 4’ deep. There are also the 83 locks. Beyond that are the marvelous creations that Pharaoh might have been proud of. There is the “Deep Cut,” a high spot in the bedrock near Pendleton where men, without the benefit of dynamite, chiseled a channel for the canal 40’ deep and 7 miles long. There is the “Flight of Five” locks climbing the Niagara Escarpment near Lockport. There is the giant aqueduct of stone crossing the Genessee River at Rochester. And, there is the “Great Embankment,” a mile long earth fill 76’ deep crossing the valley of Irondquoit Creek. These are all remarkable feats.

What makes them more mind-blowing is to consider the catalog of things these men did not have. In 1817 they did not have bulldozers (invented 1923), diesel excavators (1930’s), or even steam shovels (patented 1839). They didn’t have the aforementioned dynamite which Alfred Nobel did not perfect until 1867. There were no rubber boots (Wellingtons invented in 1852). There was no nylon rope (1940’s), no steel cable (1830’s), no really very good steel at all (Bessemer process 1855). Feeding huge numbers of men in a remote wilderness area was difficult too because there was not yet refrigeration (1856). There were no antibiotics (penicillin 1928), exactly one “sort-of” vaccine (smallpox, 1796), and no anesthetic (1842) for the inevitable amputation of infected limbs. These men made Chuck Norris look like Steve Urkel.

They worked 12-15 hour days in terrible conditions with inadequate equipment and, in most cases, for about $12 – $15 per month. The unluckiest, and there were many of these, had been lured to the United States by deceptive advertisements in Irish newspapers promising a good job with decent pay, three meals a day, and an allowance of whiskey. The workers, too poor to pay, were brought to the U.S. by the Erie canal contractors and their passage was charged against their future meager earnings, making them, immediately, indentured servants. They were basically slaves without chains.

Once the canal was completed, New York’s investment paid back, and the financiers made rich, the men who labored to build this canal did what laboring men have always done – they took a deep breath and went back to work. Because they had to. They built railroads, worked in dank mines, and dug more canals.

A canalboat (2016 recreation) in the weigh lock chamber at Syracuse. I am standing where the opening in the building is visible in the previous weigh lock building photo.

The Erie canal changed the United States. It enriched the country, it sped up western settlement, it insured U.S. dominance of the Great Lakes, and it helped to make New York City the financial and cultural powerhouse it is today. All these things were bricks in the great edifice which became U.S.A. – the Superpower. In this way the Erie canal, “Clinton’s Folly,” the little ditch, changed the world.

As I walked back to my hotel through the streets of Syracuse I thought about these men. I thought about rockets and I thought about canal boats. My thoughts drifted to the pyramids, the cathedrals, the railroads, the highways, and to all these ostensibly “good” things brought forth by men and women who got very little out of the exercise but exercise. Others with money and capital and power got more money and capital and power. As Kurt Vonnegut said, “So it goes.” And yet.

There is nobility in hard work and in struggle and in the creation of things which make the world a better place even if such benefits do not accrue to those who build them. The thing which raises human beings above the animals is not that we have iPhones, but that we can make iPhones. The Gateway Arch is a magnificent thing, but so is the Niagara Falls. What ennobles the Gateway Arch is not that it is pretty and gleaming and very, very tall, but that some man imagined it and a few men developed a plan to make it a reality, and hundreds of men and women with their hands and their feet and their brains summoned it into existence.

The Erie Canal, no less than Michelangelo’s David, was a work of art. The sacrifice of those who built it is not dimmed because their masterpiece has been superseded by bigger, better, and faster modes of transport. The nobility is in the striving, made all the more noble by the difficulty of the task. As John Kennedy said about sending men to the moon (the Saturn V) so might we say about the Erie Canal. We do these things “not because they are easy, but because they are hard.” Therein lies the nobility.

by: Dustin Joy